Broad Bay and its Boating Club to 1960

Unique in many ways, Broad Bay is fortunate in being far enough from Dunedin to have an identity of its own, yet close enough to enjoy the many benefits of the City.

More than a century ago, following the gold-rush era, and with the growing Edwardian fashion for ‘picnics and holidays’, Dunedin townsfolk became increasingly familiar with the attraction of the Bays of the Otago Peninsula. These mainly were the domain of the small farmers and landholders who had felled the bush and built homes here.

Of course, almost all communication around the harbour in the 1880s, with the town and with the very important centre of Port Chalmers, was still by water. Many Broad Bay settler families had some kind of boat, which, if Dunedin was the destination, was frequently left at one of the Company Bay inlets, while the owners walked across what is now the McTaggart Street area to avoid the winds and tides at Grassy Point.

In a community where boats are important, even if they are utilitarian, the fast, the easily-rowed, or the swift sailer is always valued and admired. Hence, it is inevitable that competition to be first to arrive, be it with cargo or passengers, develops. The sheer delight of being on the water in pleasant weather and in beautiful surroundings appeals to most people, so little wonder at the popularity of Broad Bay as an excursion or holiday venue: far enough to leave the Dunedin workplace behind and out of sight, yet near enough to be reached reasonably quickly when the break was over.

Increasingly numerous photographs towards the latter part of the nineteenth century show the locals also involved in leisure activities in our district. Work boats with oars and sails feature in local pictures of netting fish, in sailing for pleasure, or at anchor within the Bay, with the first wharf as a background.

By the 1880s regular ferry services linking Broad Bay and Portobello with Port Chalmers and Dunedin via the Eastern Channel (inshore at Grassy Point) were well-established, and with these came the weekend visitors and the day-trippers.

Quite quickly boarding-houses came into being: ‘Koromiko House’ in Broad Bay, The Retreat’ in Portobello. These catered, along with the Portobello Hotel, for the needs of visitors, and by the turn of the century Broad Bay was being called ‘The Yachtsman’s Paradise’ and ‘The Popular Holiday Resort’ on postcards showing its attractions. In the period from 1900 to the early 20s the number of holiday cribs and houses simply multiplied each year, and the popularity of Broad Bay in particular is indicated by the large number of substantial houses built here by the successful business and professional families of this era.

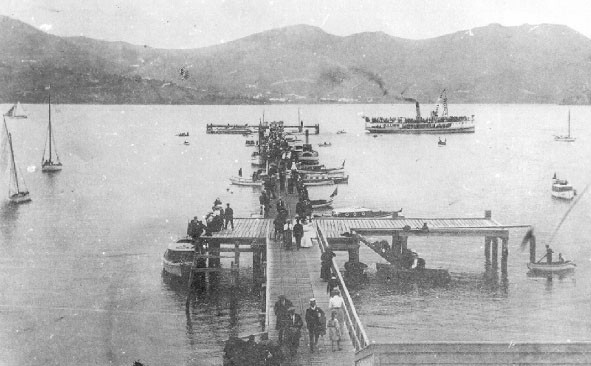

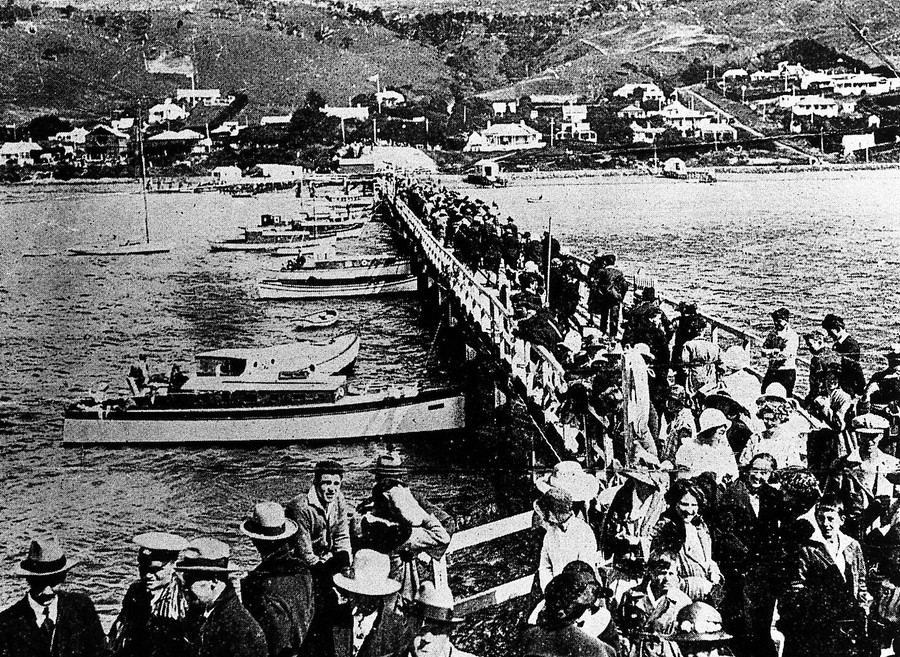

At least part of the cause of, as well as the response to, these developments, was the increasing size of the harbour ferries. From the hand-rowed boats of the watermen of the1850s, and their successors, the sailing luggers, the needs of ship-to-shore and harbour transport of all kinds of goods and passengers, were by the 60s providing employment for half a dozen shallow-draught steamers of various types and sizes. These included the well-known paddle-boats ‘Favourite’, ‘Peninsula’ and ‘Golden Age’. The 200-passenger ‘Onslo’ of 1889, and the well-remembered 110-passenger ‘Tarewai’ of 1905 were followed by the twin-screw, 230 hp ‘Matariki’ in 1908, and then three years later by the 800-passenger ‘Waikana’ and ‘Waireka’. The Broad Bay wharf was lengthened substantially to cater for the increasing draught of all these vessels, and the Ross Point wharf was built. Both provided excellent facilities in one of the most picturesque parts of the harbour and Broad Bay rapidly became the focus of major regattas which continued until the Second World war.

In this era, referred to as ‘The Recreation Period’ by Hardwicke Knight in his book ‘Otago Peninsula’, Broad Bay was simply the most fashionable harbour resort, attracting hundreds of visitors whenever fine weather and a holiday combined.

Inevitably, boats and boating activities flourished, since the wide bay, in which some shelter can always be found, is relatively free of tidal currents. As well, it is sufficiently large to enable a good triangular racing course completely visible from the shore to be laid out – a feature unmatched in any other harbourside settlement.

Of course, these factors combined to encourage some kind of organisation to promote and run suitable sporting events, and so the Broad Bay Boating Club came into being.

The Wharf (briefly)

‘The Wharf’ was once the focus of all transport and travel to and from our district. Undoubtedly there must originally have been a smaller jetty to answer the needs of loading the early boats, or of bringing goods and passengers ashore.

Clearly by 1863, when the ferry ‘Golden Age’ commenced operations, followed in the same year by the iron paddle-steamer ‘Peninsula’, a wharf of some reasonable length would have been needed.

Captain Edward Moss, based in Portobello, operated boats between there, Port Chalmers and Dunedin from 1887, and Broad Bay was included in the Eastern Channel route.

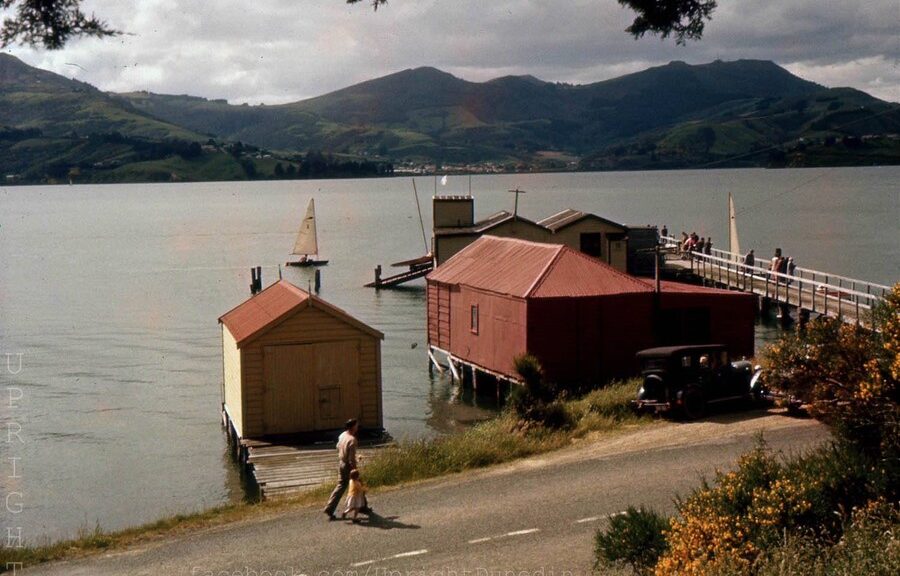

As the number, and size, of boats to and from Broad Bay increased, the wharf was widened and lengthened to its longest with the arrival of the twin-screw ferries, the ‘Waikana’ and ‘Waireka’. Interestingly, the platform on which the first of the Broad Bay Boating Club’s sheds was built was the southern portion of the ‘T’ end of the first substantial wharf (1910 – before the extension in 1911).

Photos of the time show the afternoon crowds making their way shorewards, indicating the kind of importance of, and the growth of the attraction of, Broad Bay in this era. For my own part, I remember as a five-year-old being pushed along the extended wharf on the luggage/freight trolley that ran on wooden rails the length of the structure. It was originally used for cartage between the storage shed (at the shore end) and the cross-section from which the larger ferries disembarked and picked up passengers. However, by the time I was five (1933), the ‘Waireka’ and ‘Waikana’ were lying rusting on Shelly Beach, and the trolley had become a plaything.

The Boating Club

Several features distinguish the Broad Bay Boating Club from many others. It has always been an organisation that reflects the character of the district ie it has a good mix of members of varied talents who are always prepared to pitch in and accomplish things with their own hands, with some vision and a measure of ingenuity.

This is demonstrated in several ways: the Club remains one that caters for people who basically just like ‘messing around in boats’, as well as for those whose interests range from power-boats to yachts, from competition to cruising. In addition, there is a strong, practical influence from a number of members who, over the years, have constructed all kinds and sizes of boats. And Club members have built, shifted, repaired and added to all of their clubrooms and facilities, as well as having traditionally made special efforts to cater for children and learners interested in boats and their handling.

The Origins of the Club and Building its Facilities

It would seem that the Broad Bay Boating Club as a distinct body was first formed in 1923, though clearly some kind of organisation must have arranged the major regattas that were a feature of the district from the turn of the century and are depicted in the numerous photographs and postcards that survive from its first decade.

Clearly, too, though many Peninsula families had boats that were initially used for transport and communication, the development of the district as a holiday and picnic destination meant that its popularity and its fashionable attraction resulted in boats used purely for pleasure. With the wealth that flowed from the goldfields and Dunedin’s consequent commercial expansion, many wealthy families purchased, had built or even imported yachts and launches in the style favoured in Edwardian Britain, Europe and America.

This trend continued into the 20s when a large launch, yacht, or speedboat was an important part of a holiday weekend, and was certainly used in the main event of the harbour boating calendar: the Broad Bay New Year’s Day Regatta. Many of the best-known Dunedin families of that era eg Speight, Hudson, Nees, Somerville, Sundstrum, Penrose, Begg, were all represented throughout this decade.

The regattas of the 20s often used a flagship for officials, race control etc, and even in 1966, New Year’s Day was still sufficiently important to use ‘Medora’ for this purpose and to employ the last of the Otago Harbour watermen – Bert Potter – and his launch as tender.

The committee of the boating club met, it appears, on a semi-regular basis and at venues convenient to the members. Though the depression of the late 20s is reflected in the concerns expressed in Committee Minutes of dwindling support for boating in general, there were still more than 60 separate entries in the 1935 Opening Day, when the event was but a shadow of its former size. By this time, too, it was clear the facilities for starting races, their organisation, changing, refreshment etc were essential, since the decade from 1925 onwards was a critical one for the Club, in which it evolved from an organisation that had catered largely for the needs of the affluent in the harbour’s most popular holiday resort to one which was to become completely community-based. This is not to say that the interest of many of the families referred to was not retained, it was. Also, the transition occurred and was, indeed, possible through the continued support and generosity of people like Jack Somerville, the Nees Brothers, and Hugh Speight. However, the period did mark a turning point for the Club, where local people were forced to take control if the organisation was to survive. That it did was a tribute to those mentioned and to the emerging leadership of people like Ralph Ham and Ivan Brown.

In the 30s the Club had a shed – originally a ferry wharf shelter – that in some degree catered for these new needs on a landing adjacent to the still-existing ferry wharf. This shed had been purchased and shifted from the wharf. The ferry wharf itself had once extended from the point where boats are now presently rigged right out across the Bay to a distance that equalled Cemetery Point. Contemporary pictures and postcards show the Harbour ferries at the end T junction, and the whole length of the jetty lined with pleasure boats – which seems unbelievable in present terms, but it accounted for the substantial nature of the landing onto which the first clubhouse was shifted. The jetty’s base and decking were hardwood, of the same kind of dimensions as all the then harbour ferry wharves, and had been acquired through the good offices of some of its influential members, combined with the generosity and work of the Otago Harbour Board. Unfortunately, the shed itself was not as substantial as its foundation, and was blown apart during a storm in September 1939.

The need for better accommodation had been obvious for some years, but finance was a hurdle, along with the real doubts in a small district emerging from the years of the Depression. Whereas the Annual Meeting of 1936 – held for the first time in Miss Clearwater’s Tearooms, now 690 Portobello Road – expresses satisfaction at the sound financial position of the Club, despite the decline of boating on Otago Harbour, a year later, 30/10/37, the Club was seen to be in a ‘precarious position’ through lack of local support. There were reasons: the Club was in a period of transition, and in addition it was an era of change in boating, which reflected both economics and technology. For example: just as the Edwardian custom-built keelers, typified by ‘Thelma’, had been surpassed in popularity by the ‘X’ class dinghies of the 20s – representing a more modest approach to the pleasures of yachting – so they, in their turn, in the 30s were now threatened by boats adapted to amateur construction, the ‘Idlealong’ and ‘Takapuna’ classes.

The first local boat of this new ‘Idlealong’ Class, ‘Sunbeam’, had been built in the Bay by Ivan Brown, and was so obviously successful that interest was aroused in a fast boat that was within the financial and practical reach of the amateur builder.

In 1938, under the leadership of Ralph Ham, a new direction was very definitely established. Though the Club was reported in ‘dire straits’, the decision was taken to ‘stay active’. At the same time, such was the interest in the new ‘I’ Class, that in October of that year, discussions were held on gauging local support for a ‘Queen Carnival’ as part of a drive for funds – which would be used to finance Club members to build a number of the new class of boats. The decision was taken to go ahead: groups of people sponsored various senior girls from the Broad Bay School who were, in turn, associated with various notable local boats – ‘Waiata’, ‘Dawn’. ‘Vera’ etc. The groups all set about raising funds, culminating in an evening ‘Coronation’ celebration and dance in the Portobello Hall. The affair was impressively costumed and elaborately staged, it involved the whole local community, and was spectacularly successful, raising over one hundred and sixty pounds, then a very substantial amount of money. Recognition of district participation was marked by the Club having a twelve-foot clinker dinghy built locally by Les Hogg which was presented to the Broad Bay School to assist with children’s swimming classes.

Thus, though the loss of the Club shed was seen as a disaster, finances to build one boat (R Hook) and to buy another (‘Koneke’, S Scoles), were approved.

The Declaration of War in 1939 postponed any further action on rebuilding the Clubhouse, although the damaged sections were salvaged and stored on the landing. In 1940 the Club’s assets were placed in the hands of two Trustees, Jack Price and Bert Bishop, ‘The Club to be reformed under the same constitution when a meeting is called and a quorum of six are present.’

The Post-War Rebuilding

In October 1945 activities recommenced. Led by Ivan Brown, the then-Commodore, a keen committee tackled immediately the pre-war decision of assisting local young men to construct or own suitable boats, and by November had approved two yacht loans, one to a member to build an ‘Idlealong’, the other to buy a ‘Tauranga’. As well, in the atmosphere of social optimism, immediate fund-raising activities were begun by organising a series of dances and raffles, and by Easter the next year, a regatta that held five yacht races, with catering for 200 competitors and visitors. The Club was obviously now a force within the community.

As a result of the support shown the Club, a drive to rehouse the Club was initiated, and in June 1946 a suitable building was purchased at Central Battery in Dunedin from the War Assets Realisation Board. This was promptly dismantled by club members, shifted to Broad Bay, then modified and re-erected by them on the Club’s landing. By 12/10/47 a substantial new club shed, complete with committee rooms starting box, was in place, and the Annual Meeting was justifiably seen as the occasion for celebration of a long-awaited ambition. Ivan Brown and Cyril Hart (Commodore and Vice-commodore) were complimented on their dedicated work, and thanks were sent to the local MP, Fred Jones, for his part in the achievement, which reflected the very real effort of so many people in the community.

The staging had been strengthened and substantially repiled as part of the Otago Harbour Board’s work in the repairs to the Broad Bay wharf in the same year, and a new launching ramp was constructed beside the shed. It did have the disadvantage of being steep, and it required an amount of muscle to haul the heavy boats out of the water. Despite this, Opening Day – 26/10/47 – was seen as the beginning of a new era for the Club.

Since all this involved the Club in considerable outlay, despite all work being voluntary (in traditional fashion), fund-raising was actively pursued through all the means the Club could devise. Probably the most memorable – for the many young supporters, especially – were the Boating Club Dances, held first in Broad Bay, but later shifted, because of their popularity, to Portobello and its larger hall. The net result for the community was that the Club, with its rooms, its yacht-building sponsorship, and its sailing and social activities (especially the dances), became in this period the meeting place for local teenagers, who supported it enthusiastically, so much so that such ‘activity’ was not altogether approved by some of the local church community.

The availability of storage for small boats, and even space for boat-building in the winter, greatly assisted the Club’s post-war revival, and in turn encouraged the personal building of a large number of ‘I’ class yachts by local young men, further increasing the solidarity of the Club and its group of very active supporters.

The period 1947-51 was an era of expansion for the Club which had successfully made the transition from the dismal days of the mid-30s to become a strongly-supported and entirely community-based organisation. The services of two of the leaders of this transformation were recognised when, at the 1948/49 Annual Meeting, Ralph Ham and Ivan Brown were made life-members of the Club.

Learners’ Sailing

Consolidation of this hard-won security continued with the consideration of the Club’s future, namely, the fostering of interest in boating amongst the youngsters of the community. This was done by providing learning facilities (still a continuing concern of the Club). Since times had changed, and since the School Dinghy presented in 1939 was in need of repair and thus no longer in use, it was sold. In 1950 the Club moved to buy two P-class yachts as basic training craft for learners. These were used for the next six years, though the Club learned that it had to manage and control this side of its activities. The yachts were initially available to anybody who wanted to sail them, but there were complaints after a few seasons that care was not being shown and so they were withdrawn from use. Then a new system was introduced: youngsters would apply for the use of a boat for a season, and would be responsible for its care. Interest was such that ballots were held, and this success was evident in the later building of boats within the Club by some of the boys who had had their initial sailing experiences in the two ‘Taurangas’, ‘Pixie’ and ‘Rascal’.

The 1950s

Strong Club activity continued through the early 50s when the Club rules were redrafted and up-dated. Noteworthy, too, was the generous gift of Mr Hugh Speight’s boatshed to the Club – ultimately a very significant factor in the later resiting of the Club premises and subsequent redevelopment of the whole area.

There was considerable discussion at the time of this gifting as to the purposes to which it should be put, but the idea that prevailed was the proposal that it be used to encourage general boating activities as well as yachting. It was used initially for the storage of dinghies or small powered boats, with the idea that future development of the area alongside the shed might well include slipways for launches, gear for which could be stored in the shed.

This reflects the growing generalised nature of the Club, which has always enjoyed a healthy mix in the boating interests of its members. While competitive yachting has often been the focus for the encouragement of youngsters, the ‘Competition Brigade’ have equally had their setbacks. On the occasion of the decision regarding the use of the Speight shed the minutes record: ‘More discussion broke out, heated at times, with every member expressing his opinion (sometimes all at once) until the Commodore (Gus Paterson) called the meeting to order’.

As the decade continued, a loan from the Department of Internal Affairs (which had helped finance the Club rebuilding) was repaid. ‘Idlealongs’ continued to be built and harbour yachting remained strong, but considerable changes were afoot. In this respect, mention should be made of Jim Driver, for years a member of BBBC and frequently a delegate to other clubs or associations. As a schoolboy he had become crippled by polio, losing the use of both arms. Such was his interest in boats that he persisted in an amazing manner with efforts to lead a normal life. He successively owned two yachts, ‘?’ and ‘Rangi’, that he sailed with his brother, then two power boats, ‘Gadabout’ and ‘Gadabout II’, which he had modified so that he could drive them. Not content with this, he had a station wagon adapted to foot controls, and having passed the necessary driver’s licence, he could now more easily move his boat about by trailer to take part in various boating events.

Now, though the Club still enjoyed wide support, and was able to sponsor boating and social functions that were well-supported, as the decade progressed, factors began to grow affecting the Club. By 1954 concerns were being expressed not only about the slipway -it needed to be easily and rapidly used at any stage of the tide – but also the condition of the roof. As with many war-time buildings, the roof was covered with Malthoid, which was clearly reaching the end of its life. Then, at that year’s Annual Meeting, the stability of the whole structure upon which the Clubhouse was built was brought into question. Changes to Harbour board policy, and the imminent dismantling of all unused wharves dating from the ferry-boat era were rumoured, and this was crucial in the decision to consider moving the clubhouse ashore – which would avoid the potentially crippling expenses of maintaining the large wharf structure.

Investigations were begun into the feasibility of moving the building to a site where maintenance of the piling could be handled by Club members at low tide. By the end of the year sketch plans and estimates of costs had been prepared and were presented to a special meeting. The proposal was to shift to a site opposite the bottom of Camp Road (now Camp Street) where it was felt the best depth of water, combined with firm foundation material, was available. All preparations were put in hand, and arrangements to store boats the following winter were made. The proposals included using materials from the Speight shed, to ensure the best use of all resources available. Various ideas about floating the entire clubhouse by barge to the new site were mooted and application to the OHB for the chosen site was made.

By the beginning of 1955 the Club’s proposal concerning the development of a simple monoclass yacht had come to the attention of the OYMBA, which announced its sponsorship of a ‘A One Design Class’. This was, of course, approved by the BBBC, but produced little enthusiasm from other harbourside clubs. The traditional Easter races included a power boat display and races. After this, a special meeting was held to consider the shifting of the clubhouse to its new site, for which approval had been given by the OHB. Rosters for preliminary work were made and all appeared to be in hand. However, resolve to proceed with the project faltered. Concerns about finance and club membership surfaced. Efforts were made to widen the base of support by encouraging club social activities, but the impetus to shift to the new site was lost and interest now focussed on the possibilities of establishing a monoclass yacht, proposed by Andy Wilson, to be known as the ‘Dolphin’ class. It was to be simply constructed, light, cheap to build (since by now ‘Idlealongs’ were becoming beyond the means of most youngsters), fun to sail, and would solve the crewing problems the club was experiencing, since it was a one man, one sail class of yacht. By the end of the year the first of these was under construction, and the Club had begun its ‘love-hate’ relationship with the OYMBA. The crux of this has been the fact that, over the years, the Club has often had a relatively small membership base, and the dues to the official Otago Yachting body have often been seen as too onerous, given the level of support promised, or given in return. Doubtless there have been faults on both sides, but an incident where yachts attending a regatta were not permitted to race ‘because they were not part of an affiliated club’ soured relationships for a long period, and delayed the eventual rejoining with the official body.

So: by the end of 1955, when the BBBC first resigned from the OYMBA, there were ‘Dolphins’ under construction, and the decision was taken: ‘that plans and specifications will not be issued until the present boats are finished, so that the Club has full control of the Class’.

This range of concerns: clubhouse, crewing, finance, local support, and the excitement of the potential of the new ‘Dolphins’ continued into the following year, when the pressing need to rebuild the clubhouse was again raised and the first of the new class (built by Andy Wilson and Gus Paterson) was launched on 28/7/56. Interest in the new boat was intense, since several others were being built, while in the same period the Portobello Club reopened after a lapse of some 20 years. This was welcomed, both as added local focus for the new class, and its inherent possibilities for revitalisation of boating in this part of the harbour.

By 1956, the essential formalisation of Dolphin specifications, with prescriptive weights and measurements, was established and recognised nationally. The Club received interested inquiries from as far afield as Nelson and Wellington, was itself involved in building three others, and had placed an order for sails. In October the refusal to let the Club boats compete took place, but the Bay’s association with the strengthening Portobello Club leant weight to the protest to the OYMBA, and by the end of the year reaffiliation occurred.

During this period the realisation of the seriousness of the state of the clubhouse was ever a factor in members’ minds: discussions turned from the removal to below Camp Road to being in favour of a rebuilding on the site of the Speight shed. Some roof repairs had been made to the existing clubhouse, but early in 1957 the decision was taken to start with the beginnings of the present boat launching ramp as a necessary preliminary to rebuilding the clubhouse and committee rooms. Committee meetings are recorded as being moved to Hart’s billiard room and a letter was sent to all boatowners to vacate the shed so that dismantling could begin.

By mid-1957 the new boat ramp was already well under way as the result of weekend work by club members. Here it is appropriate to record the very important contribution to the Club at this time by George Mason Snr. His special efforts and cartage of materials facilitated the work that made this big project possible. Quite often the spectacular is remembered, the most essential and basic facts forgotten, but George and his trucks really made possible the beginnings of our present facilities.

By the end of the year the shed and its platform had been dismantled and the materials stockpiled. The Committee had approved a plan for the new building and this had been forwarded to the OHB for consent and permit. Thus, racing for the coming season was from the partly-completed launching ramp.

There are several references in this period to a proposal to add a jib to the existing ‘Dolphin’ rig. This, it seems, originated with a North Island club, bit it was not adopted here. Approximately ten boats were built locally, and records show that 20 plans were printed and presumably sold, while at least four boats survive from what was a tremendously important Club project. The reason remembered for the rejection of the mainsail + jib rig was that it was seen as potentially reviving the former crewing problem in local boats, and, though it may have been used elsewhere, Broad Bay clearly wanted to maintain the strict ‘one design’ formula. This was quickly made plain to a local who had built a boat with a roll-sided cockpit when he was officially told to ‘change this, or the yacht will be ineligible to race as a Dolphin, or to be sold as one’.

By the Annual Meeting of 1959/60 the Club was in the first part of its present premises.

Boat Building and Boating Innovations by Club Members

The particular characteristics of a good mix of practically-minded people, combined with a willingness to pitch in and work together in practical projects has been referred to as a feature of this Club. And as well as the continuing amateur construction of small yachts for class racing, there have been a considerable number of larger boats built by Club members. There has always been at least one member who understood the principles of the design and practices of boat construction, and these members have helped each other with ideas and by example, along with a number of original approaches.

The era of change at the end of the 20s was also one involving radical developments in hull design. For centuries, most European boats intended for sea work had used displacement hulls of one kind or another. All sorts of ideas had been used in a quest for ease of rowing or greater speed in sailing, but the basic features of displacement hulls remained. With the rapid development of the internal combustion engine as well as their ready availability by the 1920s, these became a common means of propulsion for launches of all kinds. While the slow-revving, one cylinder (‘single-banger’ or ‘one-lunger’) petrol or kerosene engine was favoured for its reliability by fishermen of the era, many pleasure boats used converted car engines with more cylinders and greater speed potential. Important also for amateur builders was the fact that used engines from cars were readily available at reasonable cost.

Regattas of this era always featured launch races and the competition was frequently fierce. It was clear from many experiments that with more powerful engines, planing hulls had much greater speed-potential than the traditional displacement designs, and that hydroplanes with stepped hulls offered even greater promise. However, launches were an established and desirable form of modern boat in the 20s, whereas hydroplanes were comparable to today’s Grand Prix cars. Thus, when Les Hogg decided to build a fast launch in 1926, he chose a hull design by the well-known American, Hand, for a large, fast 28ft speedboat, and simply added a cabin.

Les Hogg

Les, a skilled tradesman and well-used to all aspects of wood-working, started into boat-building in an unusual way. As an apprentice he discovered that the father of a fellow workman was building a clinker dinghy. When Les expressed interest, his friend offered to take measurements of the individual planks as his father cut and fitted them; Les duplicated these and so he built his first dinghy. Soon a larger boat seemed desirable – to use Les’ words, ‘Boats were about the only thing I was interested in in those days.’ He conceived the idea of using the moulds of an ‘X’ class yacht and lengthening this to a 20ft carvel hull. This he built and powered with a 3hp single cylinder engine.

Unfortunately, in a storm the boat broke her mooring and washed ashore where she split from stem to stern into two sections. Most other people would have washed their hands of the wreck, but Les and his dad salvaged the sections and completely dismantled them. Les then reused the planks (with a larger size of fastening) to construct ‘Janet’ (‘With more substantial floors.’) and powered with a larger 4hp ‘Atlas’ engine. ‘It could really push the boat into any wind or sea!’)

Next he built his boat ‘Rambler’ at his parents’ holiday home on Ross Point. Launching it would be considered a trifle unusual these days. However, with its six-cylinder engine and its speed of 14 mph it proved a most successful performer against the more conventional displacement-hulled launches.

Soon after he bought a ship’s lifeboat, refurbished, decked and engined this to become the ‘Intrepid’. Then, as if to reinforce his statement about his interests, in 1939 he bought and refurbished a hull originally built by McPherson, who was responsible for a large number of handsome double-ended pleasure boats (‘Laura’, ‘Renown’ etc). The boat, ‘Restless’, with its pleasing lines and the beautifully-proportioned and finished deck and cabin built by Les, was a much-admired boat until it left Broad Bay in the 70s.

In addition, Les built the 12ft clinker dinghy given to the Broad Bay School in 1939. It, like all of his boats, displayed his skill and craftsmanship.

Ivan Brown

In 1936, Ivan Brown built the ‘Idlealong’ ‘Sunbeam’. It was the first on Otago Harbour of what was to be the most popular class of small yacht of the 40s and 50s, and a boat which immediately attracted attention. Fast, and exciting to race and sail, yet, at the same time, beamy, stable and comparatively roomy, it was and still survives as a good, all-round boat. With watertight bulkheads and relatively simple construction, the design survived for nearly 40 years with modification to plywood construction.

‘Sunbeam’ was the first of the Otago fleet, providing the impetus for the Club’s Queen Carnival of 1938 and the foundation of its post-war success, both with this class and its rebuilding of its premises, as well as its social impact on Broad Bay. Ivan also built ‘Omatere’, a 30ft motor cruiser, in the shed in the Bay below his home. This large and comfortable boat was certainly the most notable addition to the dwindling post-war launch fleet on Otago Harbour, and continued to be admired until it was sold outside of the Bay, probably to Te Anau.

Jim Ritchie

Three significant boats and several hard-chine dinghies were built between 1939 and 1947 by Jim Ritchie, a handyman who fully comprehended the essential business of boat design. His first boat, an 18ft carvel hull with a foredeck was intended for harbour fishing, but its converted motor cycle engine suffered from overheating problems, and the boat was sold to provide funds to start his next project, the 22ft ‘Gem’, a hard-chined planing cabin launch powered with a Crossley car engine. It performed well, but after several years he sold it to an Invercargill buyer and started into the construction of a 30ft 6” launch by the American designer, Atkin. This boat was sold as a decked-hull a year before his death, to become ‘Snow Goose’, well-known on Lake Whakatipu in the 50s, but wrecked there when her mooring broke in a storm. As well as his real understanding of the principles of the development of boat lines and their lofting, Jim displayed the real ingenuity of many of those who lived through the Depression, both hand-cutting all brass construction bolts, and even hand-making most of his copper nails.

Don Donaldson

In 1947 Don Donaldson obtained a set of lines for an English Naval Tender by JS White. These, and the descriptions of performance looked so promising that, in spite of there being no measurements except overall length and beam, he decided to build it. With advice from Jim Ritchie on design procedure, he produced full-scale drawings and a table of offsets which finally resulted in the 16ft runabout ‘Fancy Free’. This boat, with its large, open cockpit looks commonplace now, but when launched in 1949, it was quite different in appearance from the normal two cockpit design with tumble-home sterns. Performance was as described, with a speed of 26mph from a Continental Four engine. Two years later, repowered with a Ford V8, the boat was clocked at 42 mph over a measured mile, and because of its speed and cornering ability, raced frequently against hydroplanes on the Andersons Bay inlet circuit used by the Otago Power Boat Club in the 50s.

His next boat was a fibreglass version of a ‘Frostbite Dinghy’ hull, built in 1948, with advice from the late Ted George, who was also experimenting with this material.

In 1972, when trailer boats were becoming common, he built ‘Toa’, a 22ft diesel-engined motor-sailer in 14 gauge steel. In spite of gloomy forebodings from fellow sailors, this boat was completely successful. A development on the ideas of Hartley, its multi-chine construction gives enormous strength and rigidity, its absence of frames greatly enhanced space, while maximum safety is provided with water-tight buoyancy chambers. And it was all achieved at less weight than plywood construction and a building time of just over six months of spare time!

Initial information about the practicalities of this project and steel gauge etc came from the American designer Atkin, while the use of sheet materials was influenced by Andy Wilson’s experiments. Steel was chosen because of previous familiarity with welding processes, low cost, speed of construction, and simplicity when compared with the difficulty of temperature control for gluing plywood in a boat of this size in a Dunedin winter. ‘Toa’, now 20 years old (1992), is still, to all intents and purposes, as new, while a second boat, using the same design and construction, was built in Te Anau by Bruce Brown.

Alan Bain

Alan Bain, being a skilled woodworker, produced a whole range of yachts. His initial rebuilding of the ‘Idlealong’ ‘Marilyn’ to ‘Lightning’ was followed by others, then several ‘Taurangas’, as well as other classes. All of his craft were distinguished by their meticulous finishing, which did much to encourage other builders in the Club to emulate his examples.

Always determined to excel, and strongly interested in competitive sailing and its techniques, he made real contributions to ideas in the Club through his experimentation with sail shapes and forms. In an era when the average yachtie was content with, and proud of, his new set of sails from ‘Sails and Covers’, Alan wasn’t. After some frustrating racing, and sails that wouldn’t produce the wind-effective forms that he wanted, he tackled the whole problem in his own way. He threw caution to the winds, unpicking the sail panels and resewing them to get the kind of sail configuration he calculated would improve his boat’s performance. It did this, and soon others were seeking his advice on how best to get more performance out of their particular boat. This dedication to the competitive was probably the reason he was at various times a member of most of the boat clubs around the harbour, as well as others further afield.

Frank Simpson

In the late 40s and early 50s an elderly gentleman, Mr Frank Simpson, came to live close to the clubhouse. He was very interested in small boats, and though his craft were strangely unconventional – catamarans as well as monohulls – and always whimsically-named eg ‘Ho Ho’ and ‘Hah Ha’ were two examples, he did use marine plywood and glues when most other small boats and yachts were still being planked, clench nailed and screwed.

Notes by Don Donaldson (1992)