My Childhood in Broad Bay

My father was from England and my mother from Japan, so I have always liked to think that they settled between those two countries, in this lovely harbourside village, Broad Bay. My father was possibly one of longest residents of Broad Bay, living there for almost 60 years till his death in 2022. He bought the house for about 1,000 pounds on what was known as Harbour Terrace. All the roads were gravel then. It was a tiny cottage with just a scullery and a cool box for a fridge stuck on the outside of the house.

A neighbour across the road, who grew up in Macandrew Bay, lived his adult life across the road from my parents, for 54 years until he passed away shortly after my father. They used to gather for chats at each other’s places or sometimes have others join them on the road between the two houses for a great meeting and a laugh.

My father was the Broad Bay Community Centre president for a time and my parents were members of the Co-op, basically comprised of hippies loving the lifestyle that Broad Bay and Portobello provided.

My father didn’t drive, always a shocking revelation to children at school when they found out. My mother started off driving in NZ with a light blue Morris Minor, negotiating all those bends and gravel to town.

Our childhood days were spent free-ranging around Broad Bay, exploring the paddocks, streams, beach, trees and hedges, and building huts. At school, in the shrubbery, we had a village with our own leaf currency and bartered for building materials. At home, we played with our animals and made mud pies. We had a clubhouse in the back garden with several neighbour children as members. Some of my favourite activities were playing torch tag on the street after dark; sledging down the grassy paddock slopes on waxed sledges, flying downhill and trying to stop or swerve to avoid the gorse bush at the bottom; using the creepers on the trees like a trampoline. Trees were rocket ships, and inside macrocarpa hedges was another world to explore; some became huts. My parents purposely didn’t buy dolls for us girls, and so we loved playing with matchbox cars and building roads in the clay banks. We got up to mischief trying to make smokes out of dried bamboo leaves. My friend’s father smoked and had magazines of nude women, so one day we stole some of his cigarettes to experiment and giggled at the magazines in his boat shed. Suddenly we heard a noise and my friend panicked. He threw the magazines into the water and once we realised it had been a false alarm, all we could see was the naked ladies floating on their backs out of Broad Bay and down the harbour.

I would travel to town for Saturday morning music classes, getting a ride with a friend. We would sit facing each other in the back of an old jeep. We often became airborne over the peninsula’s road bumps, only to land back on the hard metal ledges. The road seemed even longer and windier as we slid from side to side and back and forth. It was a challenge to stay on our slippery seats. The back door would rattle and threaten to fling open, which it did once to add to the fear, so I would cling onto my violin like a soldier with a machine gun going to war.

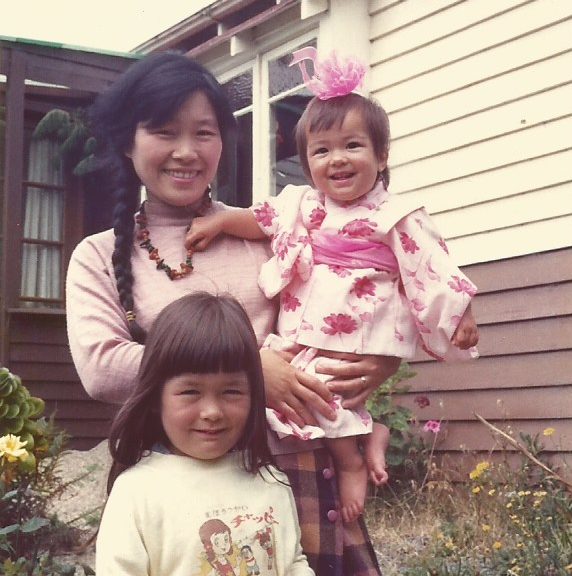

My sister and I stood out at school as we were the only Asian-looking kids. I think we were the only ones at school who travelled on a plane to go overseas. We went to Japan to visit our grandparents; it was such a different world and we would bring back things that the other children had never seen before. On the whole, people accepted us in Broad Bay. There was one time, though, that reminded me how some people thought. My sister and I was playing at our friend’s place and we all ate peanuts that we found in the kitchen cupboard. After returning home we were violently ill, and our friend was too. Our friend’s mother rang our mother asking if her son had eaten Japanese food, which might be why he was vomiting. It turned out that we had eaten peanuts laced with rat poison — stored in their kitchen.

I quickly learnt that a swift kick to ‘that boy area’ would earn me respect, so I wasn’t teased badly at Broad Bay School. This was back in the day when teachers relaxed at break times, leaving children to fend for themselves in the playground, unless there was blood — then one of us was elected to go and interrupt the teachers, who would be irritated by the disturbance. I disliked the inter-sports with Macandrew Bay and Portobello School because I couldn’t swift-kick them all. Broad Bay was the smallest school of the three so we always felt outnumbered, but I ran satisfyingly fast in competitions. We were known as the Broad Bay Beans which was supposed to be a derogatory name. Our bright yellow school t-shirts with Broad Bay School written across the chest in red did well to represent our sunny and cheerful village.

My parents did not have many biscuits or sweet foods in the house so my sister and I teamed up with other kids wanting cake: picking flowers out of old ladies’ gardens then knocking on their doors and presenting with them with a bouquet of flowers which must have been all too suspiciously familiar to them, but they kindly gave us the most delicious old-lady baking in return. I also attended Sunday School because a lady there worked at Cadbury’s chocolate factory and brought bags of seconds chocolates which we gorged on Sundays.

Our tiny house grew with our increasing need for space as my father built on additions through the years. He built a Japanese room and we could do Japanese things in it. For example, every March my mother would bring out special Japanese dolls to mark Girls’ Day. Once she invited my class to come and see the dolls and experience the treats we eat on this day. The ODT even came to interview us about Japanese New Year’s Day. The room is the place for playing my mother’s koto, a long harp-like instrument that lies on the ground. We had lots of Japanese visitors.

My parents would invite people around for a meal in the Japanese room and spend two days in the kitchen preparing food. For those not used to sitting on the floor, it must have been a great mixture of torture (pins and needles, cramp in the legs) and enjoyment (the culinary delights and amazing flavours). We had all sorts of people visiting our house: Japanese visitors and students, English relatives, archaeologists, artists and my father’s museum colleagues.

My father grew up during the war in England so nothing was wasted. He used scraps of wood and bits from the museum where he worked; he reused so many things that our house became a unique hotchpotch build. Often when my father was home alone, while we were in Japan, he would renovate, so we would come home to a new room or find the door in another place.

Broad Bay had no connected water or sewerage system until I was about 12 years old, so we grew up with a long-drop in the garden. My father designed a toilet seat in what was supposed to be the most natural sitting position for bowel motions, so guests had to be shown how to use the toilet and I seemed to be always given that job! Each time someone did their business, a scoop of sawdust was added. There were different cells underground, with each cell left to decompose for about two years, after which is was fantastic compost for the garden.

People brought the weird and wonderful to the museum and one day my father brought home a drake who thought he was a dog. He would attack us as we walked down the garden path to the long-drop. So we armed ourselves with a broom to push it away as we ran. The toilet also had spiders which my older sister feared; I used this as bargaining power when I had to accompany her to ward off the drake and the spiders.

Along with every Broad Bay kid, I learnt to conserve water. When it hadn’t rained for a while and our tanks were getting low, we used to sing a rain song in Japanese, basically along the lines of ‘Rain, rain pour down’. It seemed to work as my parents never ever had to buy water in.

Before Broad Bay was connected to the town water supply, a boy moved from town to Broad Bay School. Confident and cocky, he decided that peeing into the school’s water tank would be a great prank, but to his shock, his popularity took a dive. We Broad Bay kids knew the value of tank water. Every child shunned this boy for weeks.

Once we were connected to town supply and sewerage and got a flush toilet, I was shocked to see how much clean water it used to flush away my waste.

My teacher at the end of my final primary school year was entertaining and I don’t remember doing any real school work. He read us The Hobbit. I loved the way he gave the characters such fantastic voices and really added drama and creativity to his reading. At lunch time we built huts and climbed trees; it didn’t really feel like school. The roll was only about 40 and I had four other girls and three boys in my year. I could just walk up the road to go home for lunch.

My life changed dramatically when I started high school in town. We were the first to school as the bus came early to Broad Bay, and the last to leave school, so it was a long day for a Broad Bay teenager. Along with the girls in my year, I had decided on an all-girls school of about 1,000 pupils. We had to wear a uniform and at lunch time just sat around talking — no trees to climb and it would be hard in a kilt anyway. On the first day, my Broad Bay friends and I stayed together, scared and overwhelmed at the enormity of the school. The principal came marching down to us in the assembly hall and said. ‘You’re from Broad Bay School, aren’t you? You were taught by my husband. I’m going to keep an eye on you.’ I think we all just froze and held our breaths until she left. Through that year I realised just how little school work we had done at Broad Bay. We were also very naive about life compared to the town kids. I eventually caught up with schoolwork and realised just how lucky I was to have enjoyed the primary school years at Broad Bay.

By Yoshiko Cowell